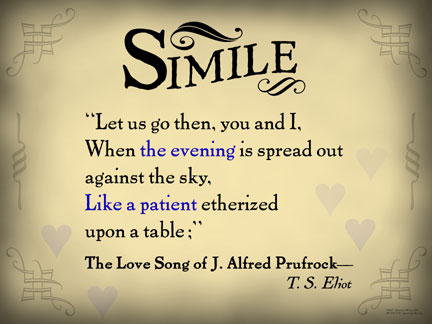

The above quote is taken from one of my favourite poems. Similes add flavour, colour, texture to poetry. But what is their purpose in philosophy?

They have received unlikely praise from the genius of logic Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein described simile as the “best thing in philosophy”. An excellent article by Yasemin Erden investigates this claim. Wittgenstein believed that similes allow philosophers to make fresh connections, and view a subject in a new light. They do this by utilising parallel cases. Knowledge we have about one of the cases can be transferred to the other. Wittgenstein also loved similes because they were free. They were not hidebound dogmatic rules. They had the potential for multiple interpretations.

That is definitely true. Plato’s similes are often excellent fun to read and seem wonderfully revealing, even to modern readers. However, I can’t help but feel as though Plato shouldn’t be using similes. To explain why not takes us into the heart of his epistemology and ontology. Plato rejects the material world because it is just an imitation of the world of the forms. He rejects art because it is an imitation of an imitation. Now, what can a simile be? The whole point of it is to reflect meaning. We aren’t supposed to see the simile as truth in and of itself. Of course we aren’t. It is true as an illustration. But… Plato hates illustration! He hates reflections and shadows. In the simile of the divided line, he describes images as belonging to the lowest epistemological realm, ranking as ‘conjecture’. Surely Plato can’t have it both ways? Either his epistemology is wrong and he can use similes, or his epistemology is right and he can’t.

Also, there a further problems with the use of simile. The fact is that their vices are the mirror of their virtues. They allow multiple interpretations because they are so vague! Arguments from simile, or analogy, or metaphor (the terminology isn’t especially important) are excellent rhetorical devices. But they don’t make for precise philosophy. Plato, such a critic of Sophists, should know that!

Here’s a silly example: “I like my coffee like I like my women – hot and black.” Here, coffee is being used to illustrate something about women. Initially it seems to be a sensible comparison. But a moment’s thought makes it look ridiculous. For example, “I like my coffee like I like my women – ethically sourced and served in a bio-degradable cup.” Or, “I like my coffee like I like my women – well educated, with a good sense of humour, and who wants to settle down and have children.” The simile in this case actually does nothing to enhance our understanding of either coffee or my taste in women.

A better example is given by Hayward et al., (2007). A prime minister might refer to austerity cuts as being bitter medicine. Yes, it hurts now, but, just like bitter medicine, the pain will be worth it in the end. Actually, in what way can global economics be compared to one person imbibing medicine? There might be a single cure for the person’s ailment, there is no known absolute cure of economic woes. Bitter medicine is unpleasant for a very short amount of time. Budget cuts might seriously affect people, families, communities, for generations. In fact, there more we look, the more we find that the ‘bitter medicine’ simile clouds reason and understanding. It is a Sophist’s trick, which is why journalists and politicians use it.

This brings me back to the main thrust of my argument. Can we really say that a simile such as the wild and dangerous beast is any less problematic than bitter medicine? People are like dangerous beasts, so they should be rounded up and put in a cage? Or they should be hunted? Or they should be fed raw meat? In a myriad of ways people are not like a wild and dangerous beast. In fact, the examples of how the analogy fails to work outnumber the ways in which it does. Plato’s use of simile, it could be argued, marks him out as a Sophist after all.